By Klaus Mönkemüller, MD, PhD, FASGE, FJGES

Professor of Medicine, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, USA

The Eye Beats Artificial Intelligence: How Biologic Chromoendoscopy Improves Detection of Colorectal Polyps

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is one of the most prevalent and fatal cancers globally, resulting in over 900,000 deaths annually. Early detection and removal of precancerous colorectal polyps through colonoscopy screening is the best prevention strategy. While finding protruding pedunculated stalk polyps and flat, plate-like sessile polyps is relatively straightforward, identifying subtle flat and serrated lesions presents a major challenge. These difficult to detect polyps have a heightened risk of progressing to cancer if missed.

New computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) systems using artificial intelligence (AI) aim to improve polyp detection rates during colonoscopy. However, even advanced deep learning algorithms struggle to identify flat and serrated polyps lacking defined shape and borders. In contrast, experienced colonoscopists can leverage specialized techniques called “biologic chromoendoscopy” to better visualize these dangerous lesions missed by technology. By recognizing natural mucus, stool, vascular, and pigmentation changes on the colon surface, biologic chromoendoscopy allows the human eye to beat AI.

Mechanisms of Biologic Chromoendoscopy

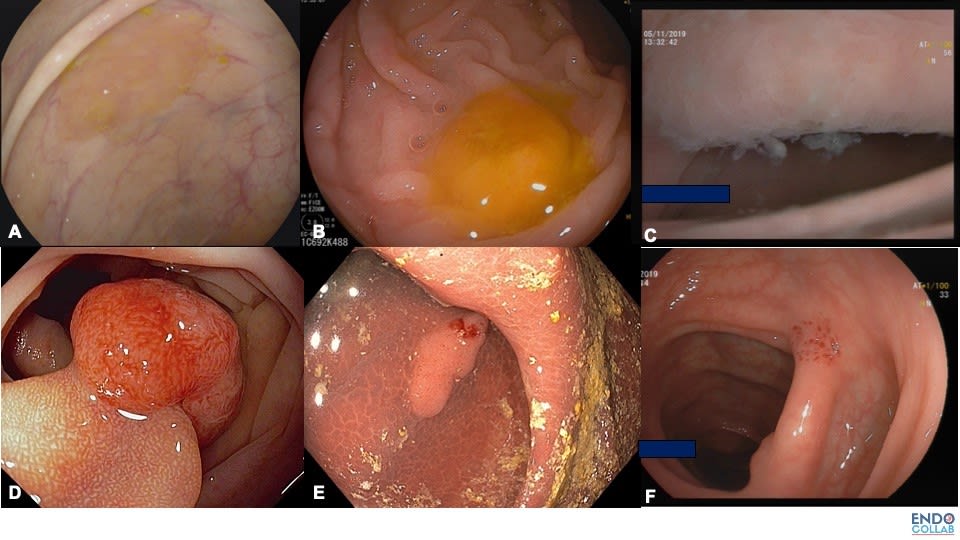

Serrated adenomas and hyperplastic polyps have an irregular, sawtooth microscopic pattern. Macroscopically, these lesions accumulate excess mucus, debris, and stool in their crypts, altering appearance.

The increased mucus affects light reflectance, making lesions appear paler than surrounding normal tissue. The mucus also traps particulate matter like debris and stool, adding hints of color. Scattered mucous filaments create a cloudy, hazy surface. Prominent ectatic vasculature results in erythematous patches. And melanin pigment deposits can darken lesions.

These diffuse changes are difficult for traditional chromoendoscopy and CAD systems to recognize. However, experienced endoscopists can leverage them through biologic chromoendoscopy to identify concerning flat lesions missed by technology.

Key Biologic Chromoendoscopy Techniques

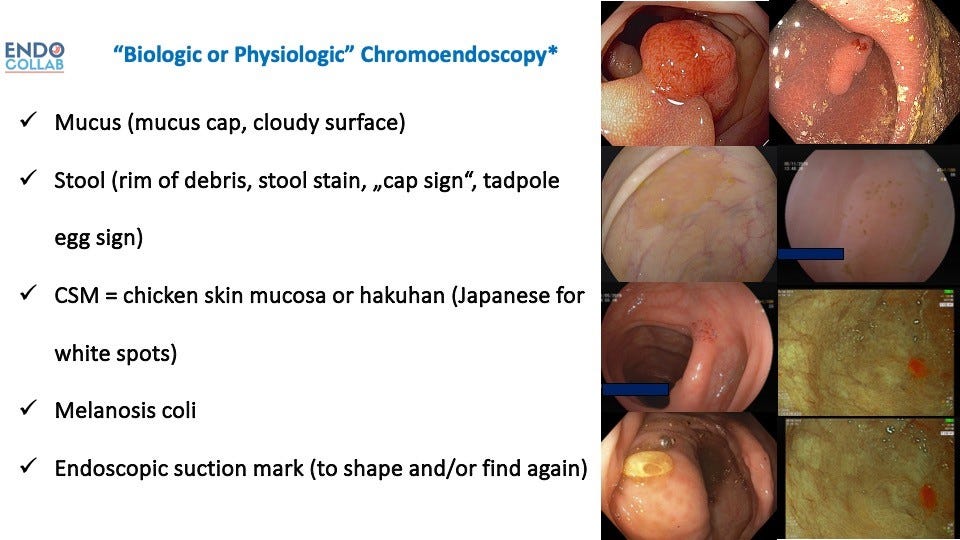

Chicken skin mucosa (CSM) refers to a white speckled appearance caused by lipid-laden macrophages accumulating in adenomas, carcinomas, and juvenile polyps. First described in Japan as “hakuhan” meaning white spots, CSM predominately occurs in precancerous sessile lesions.

Melanosis coli produces a dark black, brown, or gray discoloration from lipofuscin deposits. This condition results from chronic anthraquinone laxative use. Melanosis coli increases visibility of most polyps due to stark color contrast.

Both CSM and melanosis coli produce visual cues undetectable by AI. Careful inspection allows endoscopists to exploit these changes to detect flat and depressed neoplasms.

Advanced Recognition Skills and Applications

With experience, physicians can recognize additional subtle biologic changes to enhance polyp detection. Mucus caps reflect light, while trapped stool and debris add hints of color. Hazy mucus sheets create cloudy surfaces. Reddened patches indicate vascularity. Melanin and lipofuscin pigments darken lesions.

Skilled endoscopists also observe characteristic patterns of biologic chromoendoscopy. Serrated sessile lesions commonly have rim of mucus at edges and scattered debris on surface. Combined with CSM or melanosis coli, these signs indicate high probability of precancerous histology.

Dynamic observation after suctioning or washing can discern lesions by residual mucus or color. Serial monitoring reveals appearance changes over time, aiding detection. Targeted biopsy of concerning areas can confirm significance.

Benefits of Biologic Chromoendoscopy Technique

Mastering the nuances of biologic chromoendoscopy gives endoscopists marked advantage over AI for detecting flat and serrated polyps. Recognizing implications of mucus changes also aids lesion characterization. No algorithm matches an experienced physician’s ability to perceive subtle variations in color, light, and texture.

While CAD significantly improves adenoma detection, it serves as an adjunct rather than replacement for expert manual inspection. Biologic chromoendoscopy relies completely on the endoscopist’s intuition, experience, and real-time observation. This innate human skill exceeds current AI capabilities.

Conclusion

Biologic chromoendoscopy leverages the body’s natural mucosal changes to identify dangerous polyps missed by technology. Though AI has benefits, the physician’s eye still beats artificial intelligence through its superior ability to recognize patterns and anomalies. By honing biologic chromoendoscopy skills, doctors can optimize manual detection of precancerous lesions hidden from algorithms. Combining the strengths of human insight and AI assistance offers the best approach for reducing colorectal cancer risk through colonoscopy.

Figure 1. Personal Classification of Biologic or Natural Chromoendoscopy.

Figure 2. Various Types of Biologic or Natural Chromoendoscopy. A. Rim of stool or mucus. B.Cap of stool. C. Cloudy surface.D. Hakuhan or chicken skin mucosa. E. Melanosis coli. F.Endosocpic suction mark

References:

- Jass JR J.R. and Roberton AM., Colorectal mucin histochemistry in health and disease: a critical review. Pathol Int 1994;44; 487–504.

- Muto T, Kamiya J , Sawada T, Sugihara K, Kusama S. Clinical and histological studies on white spots of colonic mucosa around colonic polyps with special reference to diagnosis of early carcinoma. Gastroenterological endoscopy, 1981;23:2:241-247

- Shatz BA, et al. Colonic chicken skin mucosa: an endoscopic and histological abnormality adjacent to colonic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:623–7.

- Nowicki, M et al. Colonic Chicken-Skin Mucosa in Children with Polyps is not a Preneoplastic Lesion, Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2005;41:600-606.

- Nesheiwat Z, Al Nasser Y. Melanosis Coli. [Updated 2023 Feb 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493146/