By: Jonathan Rozenberg, DO, MPH, Internal Medicine Resident; Klaus Mönkemüller, , MD, PhD, FASGE (USA), FJGES (Japan), Professor of Medicine; Adil, Mir, MD, FACP

Institution: Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, VA, USA

Cameron lesions refer to linear erosions or ulcerations of the gastric mucosal folds in patients with a large hiatal hernia that are typically located at diaphragmatic pinch, often in the case of a large hiatal hernia. First depicted by Cameron and Higgins in 1986, these lesions were originally found in those who had greater than a third of their stomach above the diaphragm on a chest x-ray (1,2).

It is theorized that mechanical trauma, specifically persistent friction between the gastric folds at the level of the constriction is the most likely etiology and results in local ischemia. It has also been suggested that the pressure difference between the thoracic and abdominal cavity during respiration may lead to mucosal stress and ulceration, besides added injury from gastric acid and pressure of the diaphragm on the hernia (2,3).

Hiatal hernias are identified on esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in 0.8% – 2.9% of patients (4). Among these, Cameron lesions are identified in approximately 5% of all cases; however, the prevalence of these lesions is positively associated with hiatal hernia size and ranges from 1% – 13% in small (< 3 cm) to large (> 5 cm) hiatal hernias, respectively (2).

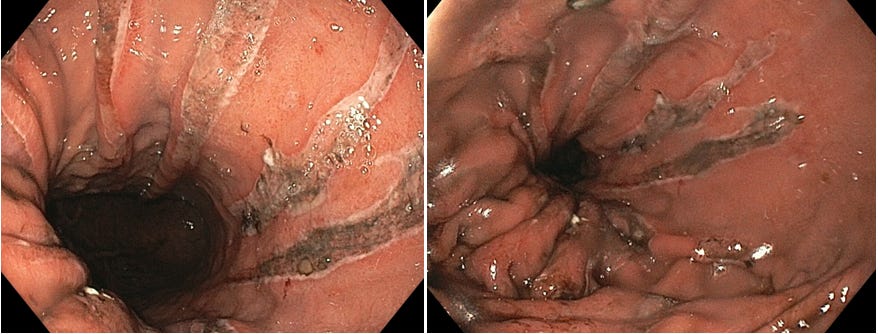

The gold standard for diagnosing Cameron lesions is EGD. On EGD, Cameron lesions are visualized as superficial, linear erosions/ulcerations on the mucosa covering the crests of the gastric folds (Figure 1); often with concurrent erythema, edema, and/or bleeding (1,2).

Figure 1: Large linear Cameron lesions associated with a large hiatal hernia

Nonetheless, it is not uncommon to miss Cameron lesions on the index EGD as they are often very small in size and without active bleeding. A recent systematic review determined that an estimated 69% of patients had undergone one or more EGDs prior to formal diagnosis of Cameron lesions (2). As such, endoscopic evaluation of patients with a hiatal hernia necessitates special attention to be paid to the hernia sac, area of the diaphragmatic pinch and the lining mucosa during both the antegrade and retroflexed view. Newer diagnostic modalities such as magnification chromoendoscopy or Narrow Banding Imaging (NBI) have been purported to assist in the identification of mucosal lesions consistent with Cameron lesions (1,2).

Medical therapy with proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) serves as the mainstay of treatment with most patients responding positively to medical therapy (1). Patients may also require additional iron supplementation as Cameron lesions can be a potential cause of iron deficiency anemia also. Among those receiving dual therapy of an acid suppressing drug and iron supplementation, over 60% of patients demonstrated healing of Cameron lesions via repeat EGD at the six-week mark (5). Interestingly, most patients with Cameron lesions possess concurrent gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with or without esophagitis and may already be on PPI therapy at time of diagnosis (1,2).

Overall, Cameron lesions are rare, benign findings often occurring in patients with a large hiatal hernia. Their prevalence is often underestimated as they can easily be overlooked, especially when small in size. Endoscopists must maintain a high index of suspicion in pertinent cases, especially in patients with large and complex hiatal hernias.