The biliary system is responsible for transporting bile from the liver and gallbladder to the small intestine to aid in digestion. It consists of a complex network of ducts that can be affected by myriad disorders. One uncommon abnormality is segmental, or focal, dilation of the bile ducts. This refers to cystic dilatation of portions of the biliary tree, rather than diffuse dilation of the entire system. There are several hepatic conditions associated with this phenomenon, including the rare congenital Caroli’s disease. In this in-depth post, we will explore the anatomy of the biliary tract, causes of segmental bile duct dilation, Caroli’s disease pathology, diagnosis, treatment, and long-term prognosis.

Biliary Anatomy

The biliary system originates with the canals of Hering, microscopic ducts within the liver that collect bile from liver cells. These lead to interlobular ducts between the hepatic lobules, then progressively larger ducts until finally forming the common hepatic duct. The cystic duct from the gallbladder joins with the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct, which leads to the duodenum.

The intrahepatic bile ducts consist of ducts within the liver tissue itself. The extrahepatic bile ducts include the hepatic ducts, cystic duct, and common bile duct located outside the liver. Dilatation can occur in both intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts depending on the underlying disease process.

Causes of Segmental Bile Duct Dilation

There are several disorders that can lead to segmental cystic dilation of the bile ducts:

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) involves chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and stricture formation in the bile ducts. This leads to obstruction and post-stenotic dilation of the upstream ductal segments. PSC is more common in men and often associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis has similar effects but arises from other conditions like chronic pancreatitis or biliary stones.

Hepatolithiasis occurs when stones form and become lodged within the intrahepatic ducts. This leads to obstruction, chronic inflammation, and dilation of the portions containing stones. It is prevalent in parts of Asia and can be associated with parasitic infections, biliary strictures, or anatomical abnormalities.

Liver fluke infections by parasites like Clonorchis sinensis, Opisthorchis viverrini, and Fasciola hepatica cause thickening and fibrosis of bile ducts, which narrows their diameter. The segments above these strictures subsequently dilate. China and Thailand have high rates of Clonorchis infection.

Benign bile duct tumors known as peribiliary hamartomas or biliary papillomatosis can also obstruct duct drainage, with upstream dilation. These tumors are believed to result from aberrant bile duct cells. Malignant transformation is uncommon.

Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilations of the extrahepatic bile ducts, usually the common bile duct. They are thought to arise from abnormal vacuolization and coalescence of the ductal epithelium, leading to cystic malformations that obstruct bile flow.

Overview of Caroli’s Disease

First described in 1958 by the French gastroenterologist Jacques Caroli, Caroli’s disease is a rare congenital condition characterized by non-obstructive segmental cystic dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. It is estimated to occur in 1 out 100,000-1,000,000 live births. The disease results from developmental anomalies of the ductal plates in the fetal liver, which later form the bile ducts.

In contrast with choledochal cysts, the malformations originate within the liver itself rather than the extrahepatic ducts. The cysts arise from saccular outgrowths of bile ducts caused by abnormal remodeling during embryologic development. This differs from polycystic disease, where cysts develop from proliferated bile duct cells.

The condition may occur sporadically or be inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern. There are often no associated risk factors, however some cases stem from congenital hepatic fibrosis. When both Caroli’s disease and congenital hepatic fibrosis are present, the syndrome is termed Caroli’s syndrome.

Signs, Symptoms and Complications

Many patients with Caroli’s disease experience no signs or symptoms for years. Often the condition is detected incidentally on imaging for other reasons during adulthood.

When symptomatic, the most common presenting complaints are right upper quadrant pain, jaundice, pruritus, nausea, and fever stemming from cholangitis. Intermittent bacterial cholangitis results from bile stasis in the dilated ducts. Portal hypertension can develop in Caroli’s syndrome.

Liver abscesses, septicemia, and sepsis may occur if repeated infections go untreated. The disease course may also be complicated by gallbladder stones, hepatitis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension. Hepatocellular carcinoma has been reported in 7-14% of adult cases.

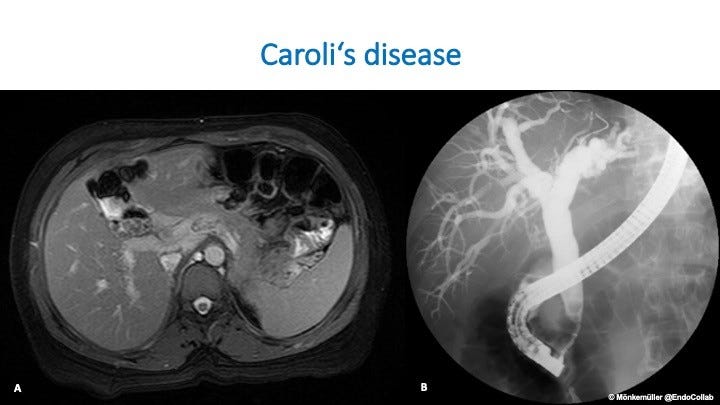

Diagnosis

Initial detection is commonly by abdominal ultrasound, which shows the characteristic focal, saccular cystic dilations of the intrahepatic bile ducts. Further imaging with CT, MRI, or MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can better visualize the cyst location and extent. MRCP provides the most sensitive, non-invasive assessment of the biliary tract anatomy.

Liver biopsy can help exclude other potential causes of duct dilation. It can also identify secondary changes like fibrosis, inflammation, and cartilage formation. Biopsy is useful in Caroli’s syndrome to determine the degree of fibrosis and portal hypertension. Genetic testing may reveal mutations linked to the disease as well.

Treatment Approaches

Treatment is aimed at preventing recurrent cholangitis and halting progression of liver damage. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are used to treat active bacterial infections. Ursodeoxycholic acid helps thin bile, improve drainage, and prevent stone formation. Aggressive cystic dilation may require drainage procedures like surgical or percutaneous drainage.

For localized disease, segmental liver resection removes the affected portions while preserving remaining healthy tissue. Liver transplantation is an option for patients with diffuse bilateral disease, recurrent infections, or secondary biliary cirrhosis. The disease has a recurrence risk of 10-15% post-transplant from the underlying biliary malformations.

Prognosis

With appropriate diagnosis and treatment of infectious complications, most patients have a normal life expectancy. Around 10% develop secondary biliary cirrhosis. Portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and complications of cirrhosis can be problematic in advanced disease. Overall, the prognosis is good for Caroli’s disease if managed appropriately.

In summary, segmental bile duct dilation has a variety of potential etiologies, including the uncommon congenital disorder Caroli’s disease. Increased recognition of this entity is key, as prompt diagnosis and treatment can significantly impact disease course. A high index of suspicion is warranted when focal bile duct dilation is identified, with thorough workup to elucidate the underlying cause.