By William F. Abel, MD, Internal Medicine Resident, and

Klaus Mönkemüller, MD, PhD, FASGE, FJGES, Professor of Medicine

Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Virginia, USA

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding encompasses hemorrhage anywhere from the esophagus to the distal duodenum due to myriad etiologies including peptic ulcers, tumors, vascular malformations, esophageal varices, hemosuccus pancreaticus and trauma. Acute upper GI bleeding is a common reason for hospitalization, carrying a mortality rate of up to 10% (1)(1). Endoscopy serves as a powerful tool in both diagnosing and treating the source of GI hemorrhage through relatively non-invasive approaches. This article delves into the latest devices and techniques now available in the endoscopist’s toolkit for tackling gastrointestinal bleeding.

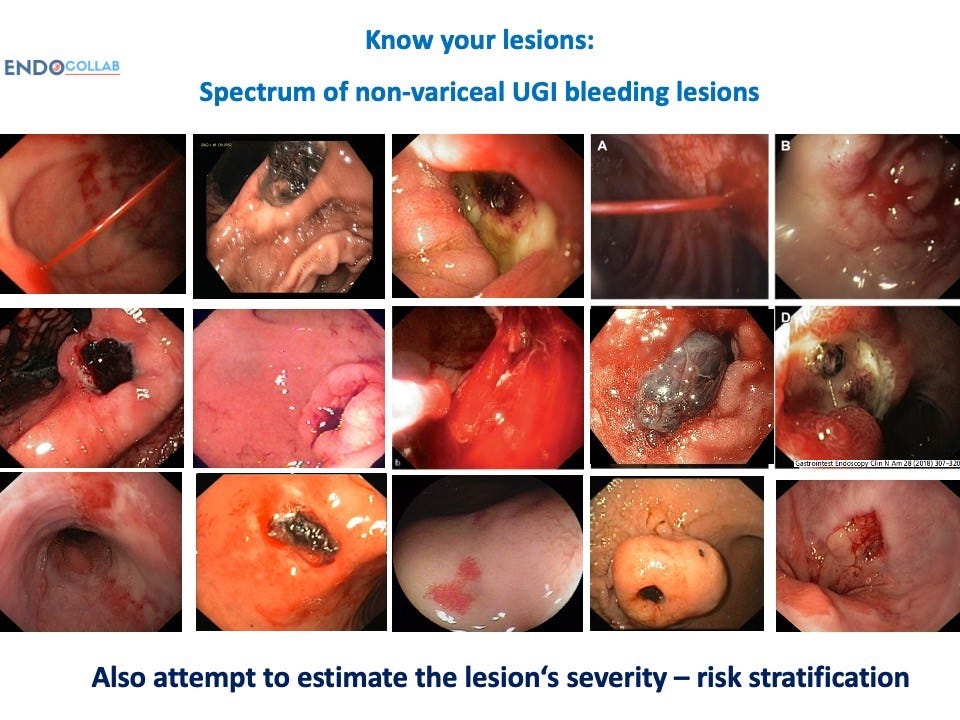

Know Your Lesions

Identifying the specific lesion responsible for hemorrhage is the critical first step in managing GI bleeding. The spectrum of potential culprits includes (Figure 1):

Image via EndoCollab.com

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) – this refers to dilated, tortuous vessels in the antral mucosa, which can ooze chronically and present as iron deficiency anemia. There are several subtypes ranging from linear striped vessels, to a diffuse honeycomb pattern, to discrete nodular lesions. Giant gastric folds and mixed morphologies also occur.

- Peptic ulcers – these can arise anywhere from the esophagus to the duodenum, but the majority localize to the stomach and duodenal bulb. Bleeding ulcers often localize to the posterior duodenal wall, presenting a challenge to target therapeutically. Ulcers can also form at gastrojejunal anastomoses after gastric bypass surgery.

- Tumors – both benign and malignant tumors of the stomach, duodenum, or colon can erode into underlying vessels and cause acute hemorrhage. Cancers of the GI tract are a common culprit.

- Dieulafoy’s lesion – this refers to abnormal subsurface arteries that protrude through tiny mucosal defects, typically in the proximal stomach, and lead to pulsatile bleeding.

- Post-surgical bleeding – this can be seen after anastomoses, gastric resections, bariatric surgery, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), and other procedures. Failure of suture lines is a frequent cause.

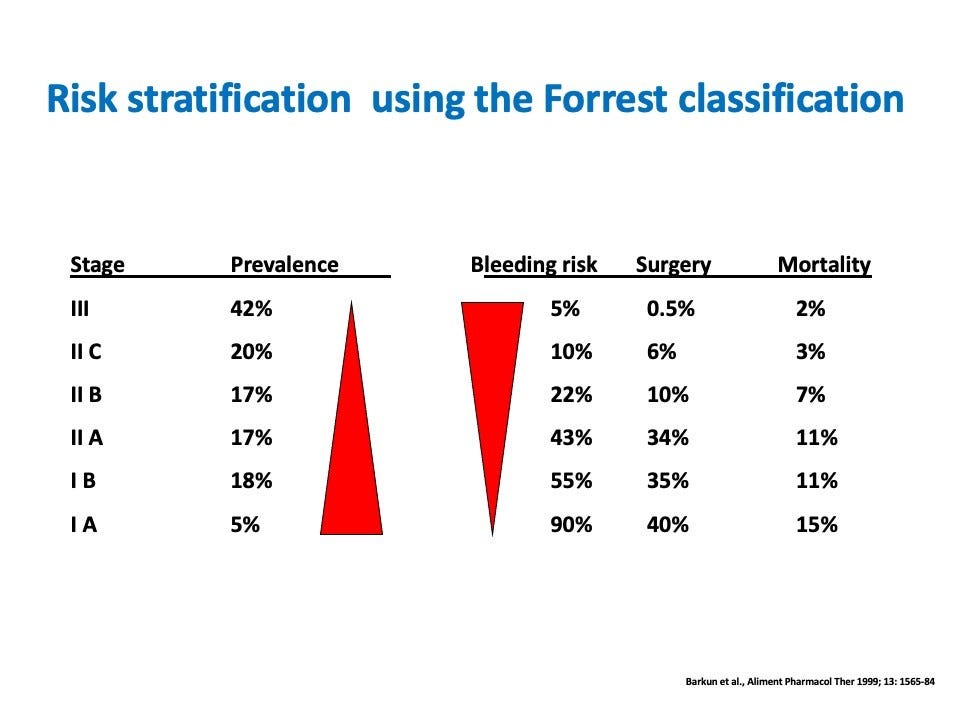

Risk Stratification

The Forrest classification stratifies lesions based on endoscopic characteristics and correlated risk of recurrent bleeding if not treated (Figure 1). For example, a spurting arterial bleed (Forrest Ia) carries a 90-100% risk of continued hemorrhage, while an ulcer with a pigmented flat spot (Forrest IIc) has only a 10-20% rebleeding risk (2,3). This provides valuable prognostic information to triage lesions requiring urgent therapy.

Traditional Therapies

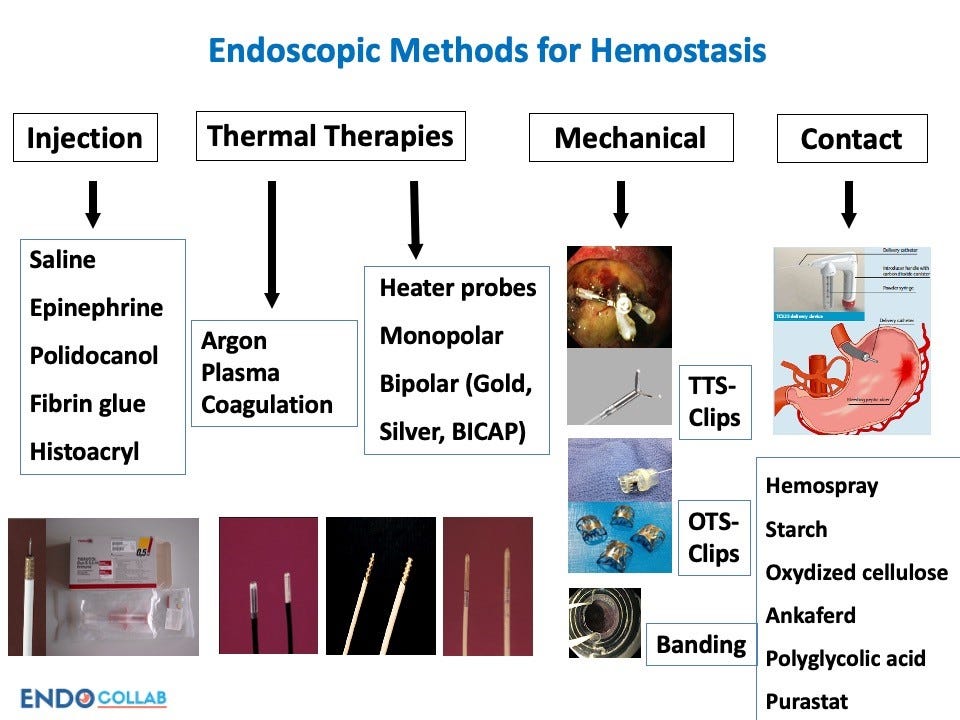

Endoscopists have several established therapies to manage GI bleeding (Figure 3):

Image via EndoCollab.com

- Injection therapy – injecting dilute epinephrine or saline into and around the bleeding site constricts vessels and slows bleeding. Fibrin glue and other inert agents can also be injected.

- Clipping – endoscopic clips provide direct mechanical compression of bleeding lesions. They come in various sizes with differing properties. Often several overlapping clips are required for definitive hemostasis.

- Thermal coagulation – using electrocautery devices to apply targeted thermal energy to the bleeding site induces vessel thrombosis and tissue necrosis to stop hemorrhage.

- Combination therapy – no single modality is universally successful, thus combining epinephrine injection followed by application of clips or thermal energy improves outcomes.

Novel Mechanical Approaches

Several innovative mechanical tools have recently expanded the GI bleed management arsenal:

- Over-the-scope clips (OTSC) – these contain superelastic nitinol alloy that allows the clip ends to be flattened into an “open bear trap” configuration (Figure 4). When deployed, the preloaded clip achieves excellent compression across a broad region of tissue. Studies show OTSC achieves hemostasis comparable to surgery for severe bleeding.

- Image via EndoCollab.com

- Endoscopic suturing – devices like the OverStitch permit endoscopic placement of suture with access to hard-to-reach areas. This allows direct ligation of bleeding lesions.

- Vascular embolization – interventional radiologists can inject coils, gel foam, particles, or liquids into bleeding vessels to induce targeted vascular occlusion under fluoroscopic guidance.

- Oxidized cellulose – substances like Surgicel applied topically interact with blood to accelerate clot formation for hemorrhage control.

Topical Hemostatic Agents

”Contact-free” modalities have emerged as another option for refractory bleeding:

- Hemospray – this bentonite powder is a naturally occurring aluminum phyllosilicate clay (similar to kaolin). This mineral powder rapidly aggregates into a cohesive barrier when sprayed onto bleeding tissue. It is deployed through a catheter passed down the endoscope. Hemospray was non-inferior to standard therapy in a randomized trial of peptic ulcer hemorrhage.

- Purastat – composed of peptides that form a viscous gel, Purastat works by forming a self-assembling nanofiber matrix that provides mechanical tamponade upon application to the hemorrhage site.

- Other powders – additional substances like TC-325 and EndoC

clot work via similar mechanisms to promote rapid clot formation.

Technical Tips and Tricks

Several techniques can improve visualization and precision:

- Distal transparent attachments – transparent caps and hoods fitted to the endoscope tip help retract mucosal folds, stabilize the scope position, expose bleeding lesions, provide compression hemostasis, and target hemostatic utensil onto the lesion (Figure 5)

- Image via EndoCollab.com

- Overtubes – these provide stability and permit repeated access to bleeding sites.

- Unique positions – adjusting scope positioning and angles can permit targeting of hard-to-reach hemorrhages.

- Traction-countertraction – applying targeted tension to tissues allows focused application of hemostatic therapy precisely on the bleeding vessel.

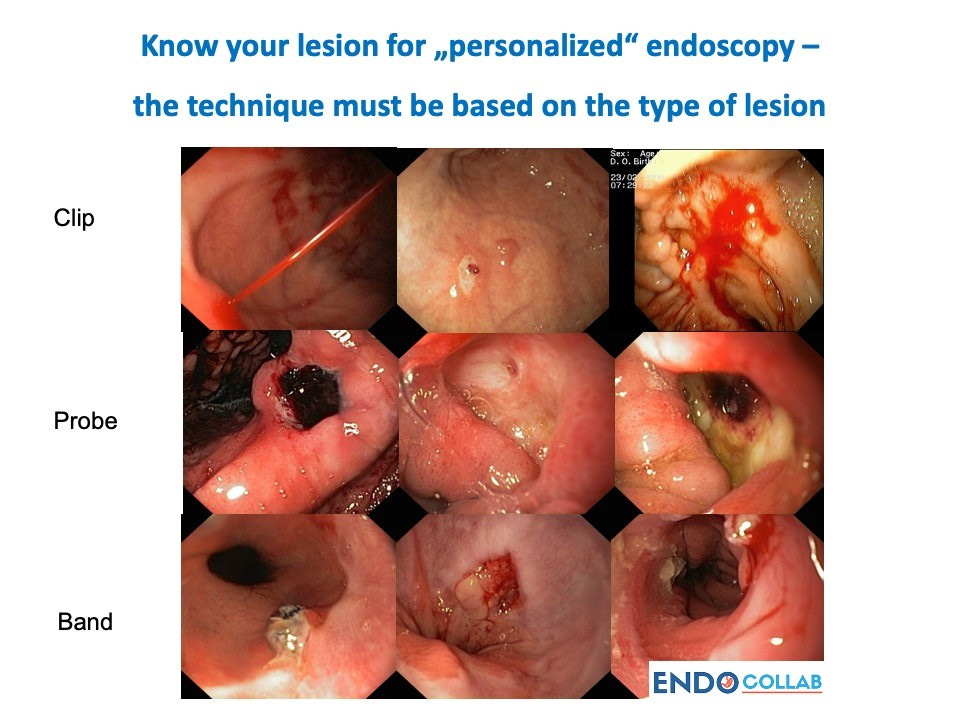

In conclusion, management of GI bleeding has advanced tremendously in recent years, with both new technologies and innovative techniques expanding the endoscopist’s armamentarium (4-61,2). The future of GI bleed care will likely involve personalized endoscopy (Figure 6) using a diverse palette of options tailored to each clinical scenario. As devices and strategies continue evolving, outcomes for this common and potentially fatal condition will continue to improve.

Image via EndoCollab.com

References:

- Hearnshaw, S. A., Logan, R. F., Lowe, D., Travis, S. P., Murphy, M. F., & Palmer, K. R. (2011). Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, diagnoses and outcomes in the 2007 UK audit. Gut, 60(10), 1327–1335. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.228437

- Laine, L., & Peterson, W. L. (1994). Bleeding peptic ulcer. The New England journal of medicine, 331(11), 717–727. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199409153311107

- Hadzibulic, E., Govedarica, S. (2007). Significance of Forest Classification, Rockall’s and Blatchford’s Risk Scoring System in Prediction of Rebleeding in Peptic Ulcer Disease. Acta Medica Medianae, 46(4), 38-43.

- Mönkemüller, K., & Soehendra, N. (2019). Endoscopic treatments for gastrointestinal bleeding: a story of cleverness and success. Endoscopy, 51(1), 5–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0790-8509

- Mönkemüller, K., Martínez-Alcalá, A., Schmidt, A. R., & Kratt, T. (2020). The Use of the Over the Scope Clips Beyond Its Standard Use: A Pictorial Description. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America, 30(1), 41–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2019.09.003

- Martínez-Alcalá, A., & Mönkemüller, K. (2018). Emerging Endoscopic Treatments for Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage. Gastrointestinal endoscopy clinics of North America, 28(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2018.02.004

This manuscript is based on a transcript of a lecture given by KM during the Dominican Congress of Gastroenterology, 2023